低氘氫水實驗室 研究項目

- 極超高純氫氣研究—7N、8N維米製程氫氣

- 固態儲氫器研究、太空船用固態儲氫器研究

- 低氘飽和氫水製程研究及應用研究

- 低氘水用於生物實驗及製藥應用研究

- 氫氣呼吸之劑量及物理效應研究

- 低氘水用於育苗育種農業生技研究

- 氫氣用於食品科學研究

- 低氘水用於食品科學研究

- 呼吸氫氣及低氘飽和氫水之於癌症、中風、巴金森症、妥瑞症、糖尿病、心肌損傷、肝損傷、腦中風、放射治療損傷、老年癡呆、心肌硬塞、痛風、COPD、異位性皮膚炎、僵直性脊椎炎、過敏、紅斑性狼瘡及自體免疫性疾病之觀察研究

用电邮传了一篇科研報告给你。

里面提到,腫瘤细胞比正常细胞消耗更多的dao, 用來快速複制。

降低细胞内D/H比会降低複制速度或停止複制。

人体能正常接受的D/H比是几百万年耒進化的结果。

推論,

癌症病人的D/H比,离开了健康状况的平衡点,腫瘤细胞比較容易取得更多的dao(氘),用來快速複制。

飲用DDW使D/H比低於原來的,正常的平衡点以下,破坏癌细胞快速複制的(重要)條件之一。

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/etm/1/2/277

细胞分裂对细胞内氘浓度的变化很敏感,正常浓度的氘是启动和维持正常细胞生长的必要条件(14)。我们的结果似乎支持Laskey等人的假设,他假设动物和植物细胞中都存在检测氘浓度变化的机制(19),必须达到细胞内D/H的阈值才能启动细胞分裂。当细胞在低氘浓度的培养基中培养时,由于达到适当的D/H比所需的时间增加,细胞的增殖受到抑制。在高等生物体中,经过数百万年的发展,对细胞内D/H变化非常敏感的调节系统对细胞内D/H的变化非常敏感。正常情况下,D/H比值比肿瘤细胞增加得更快(19)。我们观察到DDW对肿瘤细胞的体外增殖有抑制作用,而正常细胞的增殖则不受抑制,提示DDW可能影响肿瘤细胞的D/H比值,进而影响肿瘤细胞的生长速度。

Lung cancer is one of the leading causes of death by cancer worldwide; approximately 80% of lung cancers can be histologically classified as non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs). Most patients present with locally advanced (37%) or metastatic (38%) disease at the time of diagnosis (1). Despite advances in chemotherapy, the average 5-year survival rate for patients with advanced NSCLC remains extremely poor (2), thus new agents are needed to establish an effective therapeutic strategy against NSCLC. There is great interest in developing new preventive and anti-tumor agents that are more effective and less toxic. It has recently been suggested that deuterium-depleted water (DDW) may play a potentially beneficial role in cancer prevention (3).

In nature, the ratio between deuterium and hydrogen (D/H) in ordinary water is approximately 1:6600 (4). It has been known for decades that the mass difference between hydrogen and deuterium leads to differences in the physical and chemical behavior of the two stable isotopes (5,6). In biological systems, the effect of replacing hydrogen with deuterium has also been well documented (7,8). Early studies revealed that the life span of mice with ascites tumors was prolonged by drinking 25–30% deuterium water (deuterated water) (9), and the mortality caused by 60Co irradiation in mice was significantly decreased by drinking 30% deuterated water (10). Gross and Spindel discovered that high concentrations of deuterium in water induced stagnation mitosis (11). Although the high concentration of deuterium in water was able to inhibit cell proliferation by mitosis arrest and to protect the cell from radiation, it also reduced the life span of mice and even resulted in death (12,13), which limits its clinical application.

To date, research into the effects of deuterium in organisms has focused primarily on deuterated water; little research has been conducted on DDW. The possible role of naturally occurring deuterium in biological systems was first investigated in the early 1990s. DDW was shown to significantly decrease the growth rate of L929 fibroblast cell lines in vitro, and also inhibit tumor growth in xenotransplanted mice (14). Scientists have recently reported the anti-tumor characteristics of DDW when the deuterium volume fraction in normal water was reduced by 65% (15–17); however, the mechanism underlying the anti-tumor effect of DDW is still unknown. In this study, we investigated the in vivo and in vitro effects of DDW on the growth of human lung cancer and the possible mechanisms of these effects.

DDW was provided by Shanghai Chitian DDWater Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A549 and H460 cells were purchased from the Cell Research Institute of the Chinese Medical Research Academy (Shanghai, China), and human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HLF-1 cells) were purchased from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China).

The human lung carcinoma A549 and H460 cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Si Jiqing, HangZhou, China) at 37°C in 5% CO2. For in vitro studies, the cells were seeded in 25 ml cell culture bottles and grown in complete medium to 90% confluence. Then, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in 6 ml of serum-free medium containing DDW.

HLF-1 cells were maintained in α-MEM medium (Genom, HangZhou, China), containing 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2.

The cytotoxicity of DDW was measured in A549 and HLF-1 cells every 2 h for 24 h by the 3-(4,5-dimethyldiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium-bromide (MTT; Kai Ji Co. Ltd., Nan Jing, China) colorimetric assay. A preliminary study was conducted to determine the optimal concentration of DDW and the length of treatment. A549 and HLF-1 cells were cultured in DDW (25, 50 or 105 ppm) and normal water in 96-well plates at 2×104cells/100 μl well or 1×104 cells/100 μl well, respectively. Cytotoxicity was determined 24, 48 and 72 h after treatment. The MTT proliferation assay is based on the ability of mitochondrial dehydrogenase in viable cells to convert the MTT reagent into a soluble blue formazan dye. At the end of the culture period, 50 μl of the MTT reagent was added, and cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After removal of the culture medium, cells were lysed with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to determine the amount of formazan product. The dishes were placed on a shaking platform until the formazan crystals were dissolved. Absorption was measured by a microplate reader (Multiskan MK3; Shanghai, China) at 550 nm, and the results were expressed as percent decrease in cell viability compared to the controls (3). Each cell sample was measured three times, and the mean was reported.

A549 monolayer cells were treated with DDW at 50±5 ppm for 10 h, 72 h or 40 days and subsequently collected and fixed with 25% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 2 h. A549 cells were fixed with osmic acid and dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions before embedding. After staining, samples were analyzed using TEM (CM 120; Philips, The Netherlands).

After incubation with 50±5 ppm DDW for 40 days, changes in morphology and structure of A549 cells were observed by fluoroscope microscopy (Olympus, Japan). In addition, membrane morphology was observed by SEM (Multimode Nanoscope IIIa; Digital Instrument Co., USA). For SEM, A549 cells were collected and seeded on a glass overnight and then fixed for 15 min with 0.25% glutaric dialdehyde. Cells were dried and sprayed with gold after dehydration.

Cells were harvested by trypsinization after DDW treatment (10 or 72 h), washed twice with PBS and then re-suspended in ice-cold PBS and fixed with 70% ethanol. After the ethanol was removed, the cells were washed once in PBS. The cells were then centrifuged, and cell pellets were re-suspended in 1 ml propidium iodide (PI)/Triton X-100 staining solution (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, 0.2 mg/ml RNase A and 10 μg/ml PI) and incubated at least 30 min at room temperature. The stained cells were analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer in combination with BD Lysis II software (BD Co., USA).

Cells were treated with 50 ppm DDW for 48 or 72 h, seeded on polylysine-coated slides, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS for 1 h at 25°C, and then permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0). DNA fragmentation was detected using a TUNEL detection kit (Kai Gene, Nan Jing, China), which specifically labeled the 3′ hydroxyl terminus of DNA strand breaks using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated dUTP. DNA was also labeled with FITC DNA-binding dye for 5 min. FITC labels were observed with a fluorescence microscope. As a positive control, A549 cells were incubated in culture media without DDW for 48 h and treated with DNase I. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as the number of apoptotic cells divided by the total number of cells.

A549 cells were treated with 50 ppm DDW for 10, 24, 48 or 72 h. DNA and the DNA marker TrackIt 1 kb Plus Ladder (Kai Gene) were separated on 1.5% agarose gels.

Male BALB/c nude mice (weight 20±2 g) were purchased from the ShangHai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The 8-week-old mice used in this study were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment. Animal care and maintenance were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by Long Hua Hospital, Shanghai, China.

For in vivo studies, the mice were randomly divided into two groups of 8 animals each; the model group and DDW-treated group. The model group mice and DDW-treated group mice drank tap water and DDW, respectively. To construct the H460 xenograft model, cells were harvested after 14 days by trypsinization, washed twice with PBS and re-suspended at 1×107 cells/ml. Approximately 2×106 H460 cells were injected subcutaneously into the right hind flank of all mice. Animals were provided with DDW or tap water continually until the end of the experiment.

Experimental pulmonary metastases were established by inoculation of 2×106 H460 cells. Two months later, the H460 xenograft model mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were weighed. The tumor inhibition rate was calculated using the following formula: tumor inhibition rate = (tumor weight of control group – tumor weight of treatment group)/tumor weight of control group × 100%.

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences between groups were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Student’s t-test. Analyses were performed with SPSS software version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

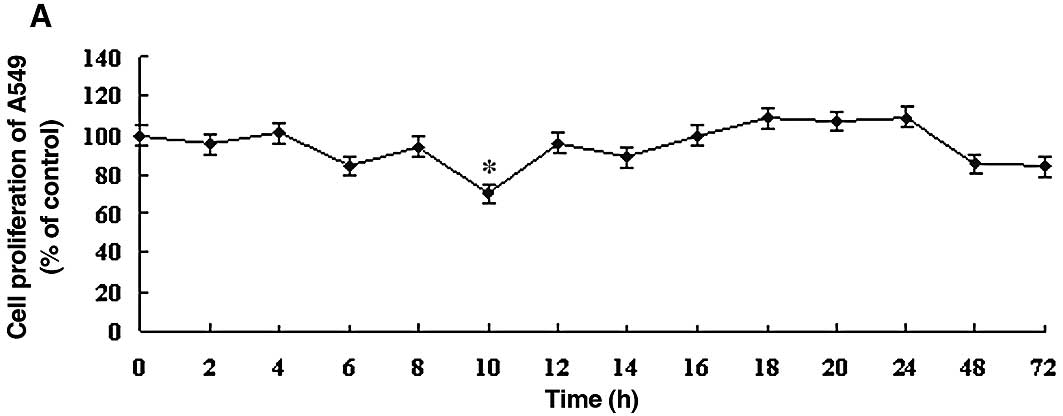

To determine the optimal DDW treatment in the A549 human lung carcinoma cell line, the effect of DDW was assessed using the MTT cell proliferation assay. The effects of DDW on the growth and functional integrity of A549 cells are shown in Fig. 1. There were no significant changes in the growth rate until 10 h of exposure to DDW. At 10 h, cell viability of the treated cells (25, 50 or 105 ppm DDW) decreased significantly to 70.39, 68.93 and 69.90%, respectively, compared to the untreated controls (Fig. 1). The cell growth rate subsequently returned to the level of the controls at 48 h. After 72 h, cell viability at different DDW concentrations decreased to 84.11, 75.23 and 86.44% of control cells, respectively.

|

Figure 1.DDW inhibited the growth rate of A549 cells. Cells were treated with DDW for different times and at various concentrations: (A) 25, (B) 50 and (C) 105 ppm. The cell growth was determined using the MTT cell proliferation assay. Results are expressed as the percentage of cell growth relative to the untreated control cells. The data are presented as mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. control. |

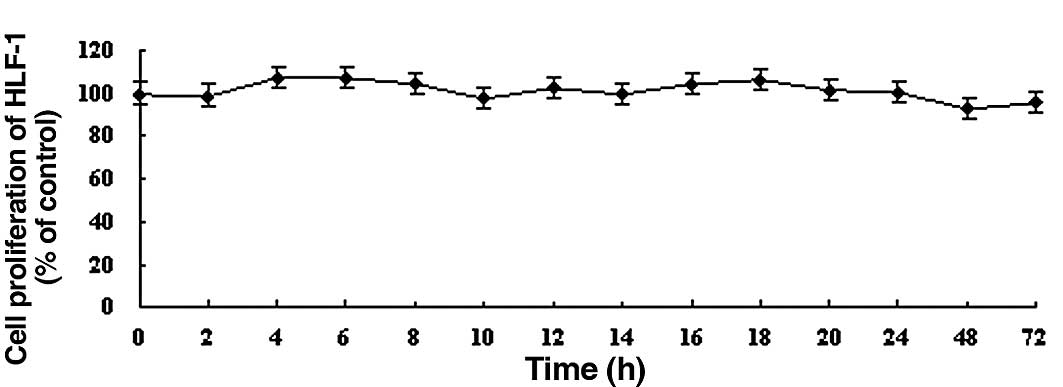

In contrast, DDW did not significantly alter the growth of human embryonic lung fibroblast HLF-1 cells compared to controls during the 72 h treatment (Fig. 2). Based on these results, we chose to use 50 ppm DDW and A549 cells for subsequent experiments.

|

Figure 2.The effect of DDW on the growth of HLF-1 cells. Cells were treated with DDW for different times and at various concentrations: (A) 25, (B) 50 and (C) 105 ppm. The cell growth was determined using the MTT cell proliferation assay. Results are expressed as the percentage of cell growth relative to the untreated control cells. The data are presented as mean ± SD. |

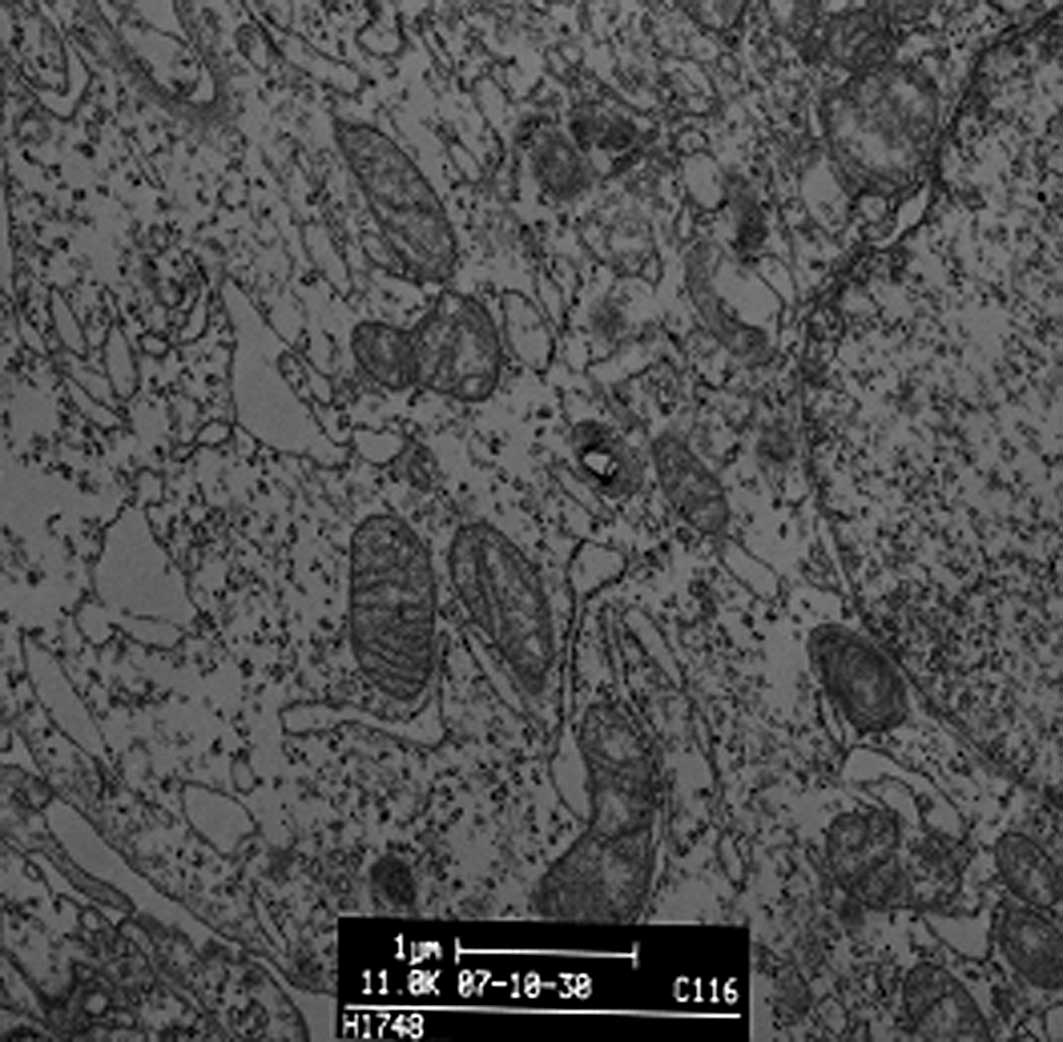

We observed the morphology and structure of A549 cells by TEM. Untreated A549 cells showed a flattened profile of cell morphology. There were no alterations to mitochondria, rough or smooth endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lamellar bodies or karyon (Fig. 3A). To observe DDW-induced morphological changes, we incubated A549 cells with 50±5 ppm DDW for 10 or 72 h. After a 10-h treatment, a few myelin bodies and physalides were observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B), and more myelin bodies and physalides were apparent after 72 h of treatment.

|

Figure 3.Representative transmission electron microscopy images of A549 cells treated with DDW for 10 h, 72 h or 40 days. (A) Control group (magnification x11,800), (B) 10-h DDW treatment (magnification x6500), (C) 72-h DDW treatment (magnification x6500) and (D) 40-day DDW treatment (magnification x8480) (A, bar=1 μm; B, C and D, bar=2 μm). |

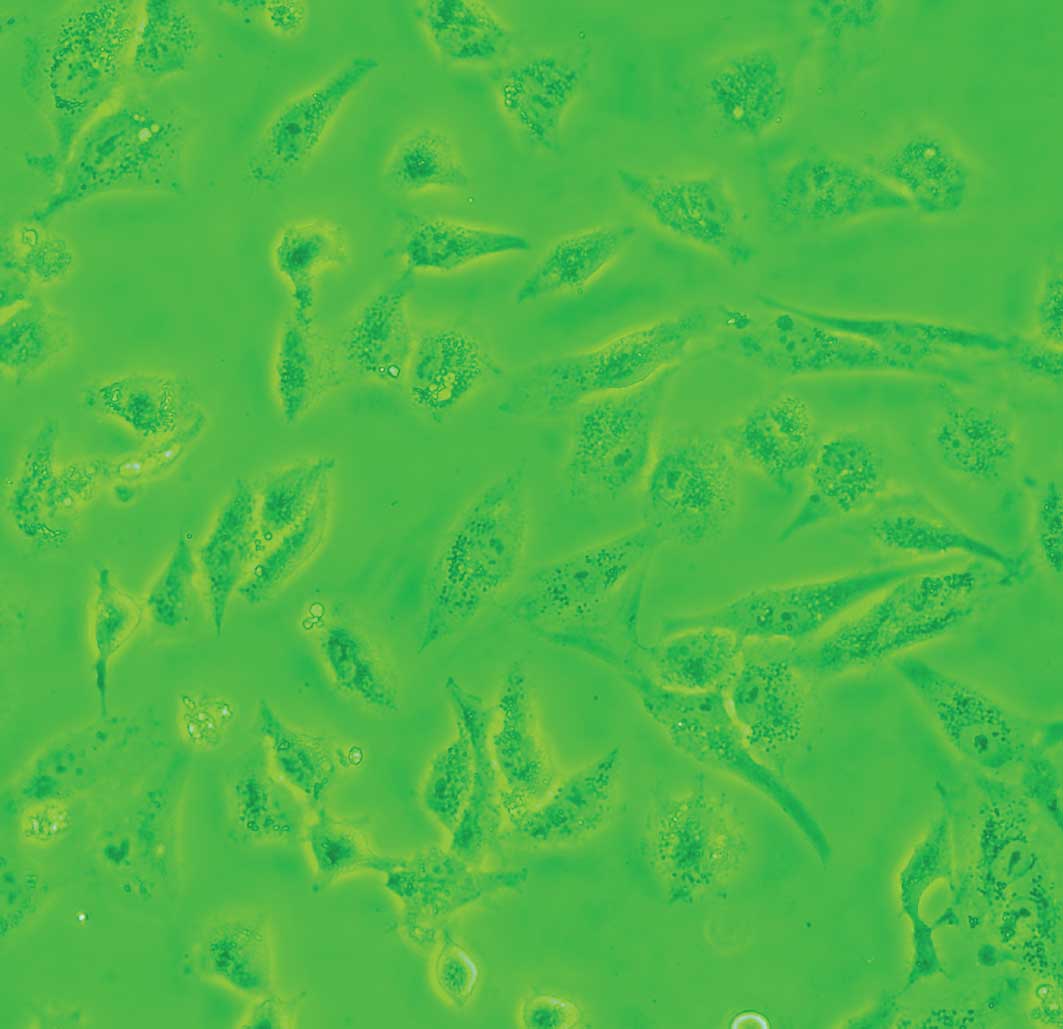

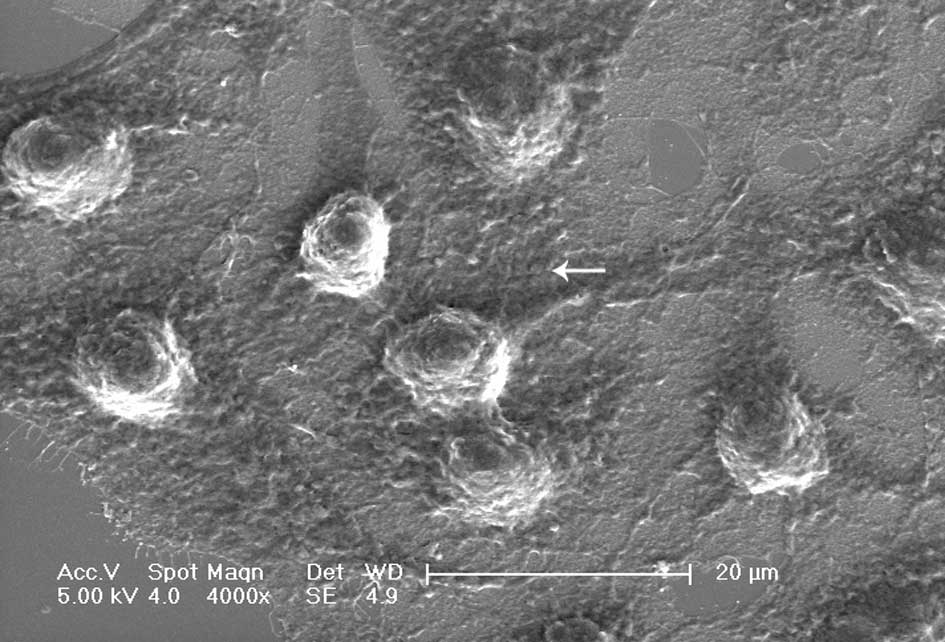

Cells exposed to DDW exhibited modified morphology, which was more pronounced after 40 days of treatment. Untreated control cells were shuttle-shaped or kidney-shaped (Fig. 4A), but they changed to an amorphous polygon when treated with DDW (Fig. 4B). Using SEM and TEM, we observed submicroscopic changes in the morphology. Under SEM, untreated control cells showed a smooth profile and more extracellular matrix than those exposed to DDW (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, A549 cells exposed to DDW had a rough profile and numerous microvilli on the cell surface (Fig. 5C and D). Under TEM, DDW-treated cells showed numerous myelin bodies in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3D); however, these changes were not observed in the control cells.

|

Figure 4.Representative microscopy images of A549 cells treated with DDW for 40 days. Compared to untreated control cells cultured in RPMI-1640, cell morphology was modified by incubation with 50±5 ppm DDW. Magnification ×640. |

|

Figure 5.Representative scan electron microscopy images of A549 cells. A and B (magnification ×4000 and ×8000, respectively) display the shape of normal A549 cells. C and D (magnification x4000 and x8000, respectively) display the cells modified by treatment with DDW for 40 days (A and C, bar=20 μm; B and D, bar=10 μm). Arrows point to microvilli. |

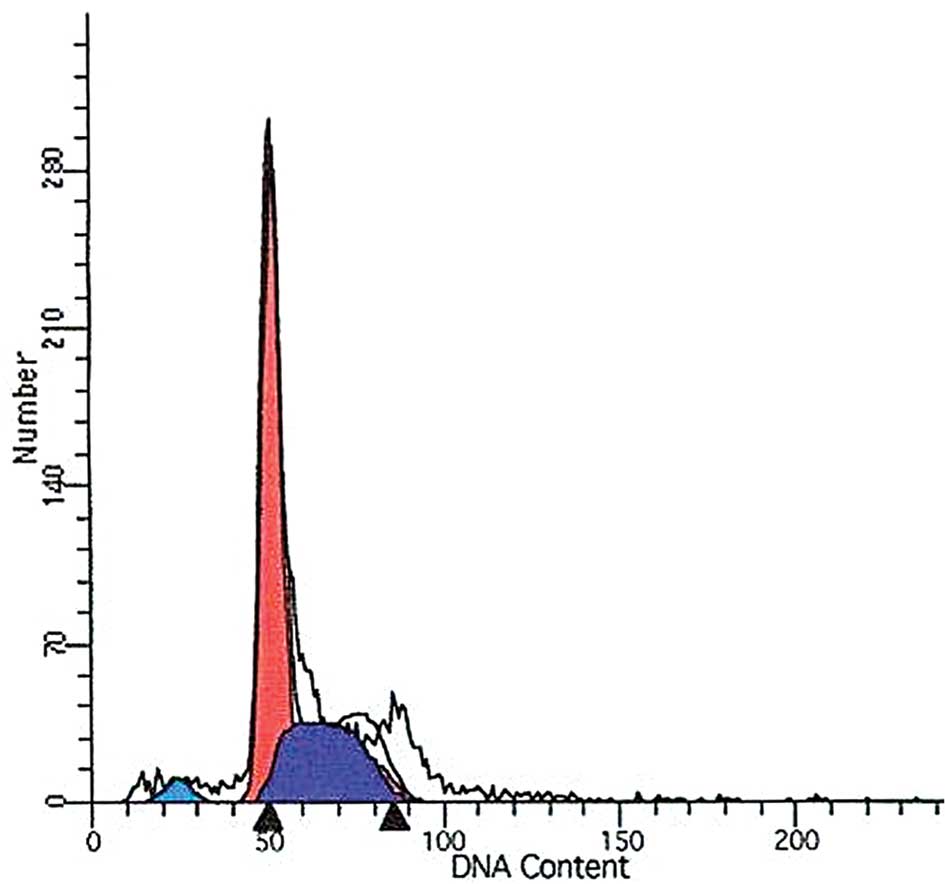

To determine whether DDW alters the cell cycle in A549 cells, we stained the cells with PI and used flow cytometry to assess the sub-G1 population. Whereas no significant changes were found in the proportion of cells in the sub-G1 phase between the control cells and DDW-treated cells at 10 h (3.24 and 4.41%, respectively), a significant increase in the proportion of cells in the sub-G1 phase was observed in cells treated for 72 h (6.24 vs. 3.24%; Fig. 6). Meanwhile, cell cycle alterations in DDW-treated cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The S phase increased whereas the G0 to G1 phase and G2 to M phase were reduced in DDW-treated cells compared to the control cells (Table I; Fig. 6).

|

Figure 6.Cell cycle analysis of DDW-treated A549 cells by flow cytometry. The percentage of non-apoptotic and apoptotic cells in each cycle was observed by flow cytometry. The data is presented as mean ± SD (n=3). (A) Control group, (B) 10-h DDW treatment and (C) 72-h DDW treatment. |

Table I.Cell cycle population in A549 cells (mean ± SD). |

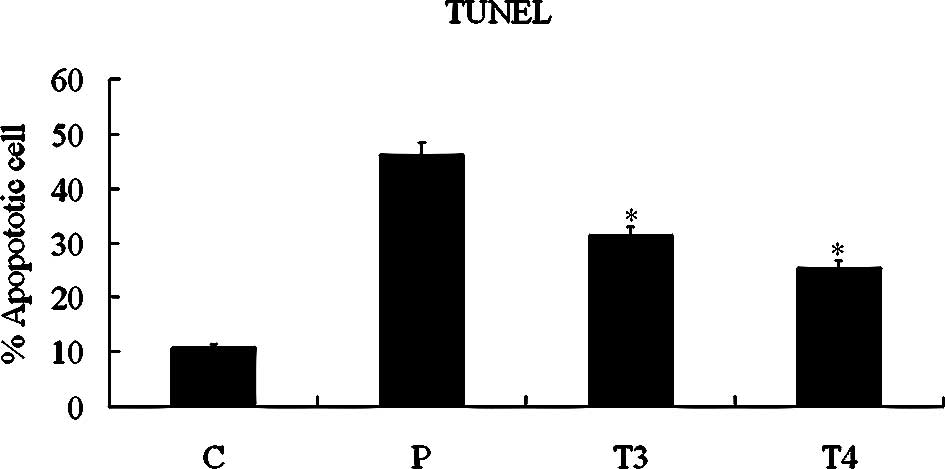

To ascertain whether DDW induces apoptosis in A549 cells, we treated cells with 50 ppm DDW and observed DDW-induced apoptosis with the TUNEL assay (Fig. 7A). Apoptosis was evident in 31.39±2.54% of cells at 48 h and 25.38±3.90% at 72 h. The increased apoptosis was significant compared with the untreated control group (10.87±1.11%; P<0.05, Student’s t-test). DNA was extracted and analyzed by electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 7B, fragmented DNA was observed in cells treated with DDW for 48 or 72 h.

|

Figure 7.Assessment of cell apoptosis by TUNEL (A) and DNA fragment (B) analyses. A549 cells were treated with 50 ppm DDW for 10 (T1), 24 (T2), 48 (T3) or 72 h (T4). C, control group; P, DNase I-treated A549 cells as positive control (*P<0.05 vs. control). |

We investigated whether DDW inhibits the growth of transplanted tumors in mice. After drinking DDW for 60 days, tumor growth in nude mice was considerably reduced. We observed a significant decrease by 30.80% on tumor inhibition rates in the DDW group (Table II).

Table II.Tumor weight and inhibition rates of nude mice. |

In this study, we investigated the in vitro effects of DDW on growth rate, morphology and structure of cells, cell cycle distribution and apoptosis. We found that DDW significantly suppressed the proliferation of A549 cells at 10 h. This inhibitory effect disappeared from 12 to 24 h, but returned during the prolonged 48- or 72-h treatment. In contrast, DDW exerted no significant effects on HLF-1 cells, indicating a cell-specific response to DDW treatment or a more rapid adaptation for HLF-1 cells compared with A549 cells.

A previous study demonstrated that 30 ppm DDW significantly decreased the growth rate of L929 fibroblast cells and also inhibited tumor growth in xenotransplanted mice. Deuterium is crucial to the start of cell proliferation as the lag period is 6–8 h longer in medium with low D content (14). DDW also affects seed germination; inhibition of germination was highest 5–6 days after the beginning of germination, but the inhibition was not observed after 10–12 days (18). In addition, the biological effects of DDW on plant cells were investigated in a previous study. In the first half hour of DDW treatment, plants showed biochemical changes similar to those induced by dark treatment; respiration increased, photosynthesis stopped and intracellular pH became alkaline, whereas extracellular pH became more acidic. Maximum effects were noted 30 min after treatment, and then cells gradually returned to normal (19). The results in the present study are remarkably similar to those of previous studies.

Cell division is sensitive to intracellular changes in deuterium concentration, and a normal concentration of deuterium is essential to initiate and to maintain normal cellular growth (14). Our results appear to support the hypothesis of Laskey et al, who hypothesized that mechanisms exist in both animal and plant cells that detect changes in deuterium concentration (19). It is necessary to reach the threshold of intracellular D/H to initiate cell division. When cells are cultured in a medium with low deuterium concentration, proliferation is inhibited due to the increased time required to reach the appropriate D/H ratio. In higher organisms, a regulatory system has developed over millions of years, which is sensitive to intracellular changes in D/H. The D/H ratio can increase more rapidly in normal than in tumor cells (19). Tumor cells have a higher growth rate than normal cells as a result of consuming a greater quantity of deuterium (20). We observed that in vitro proliferation of tumor cells was inhibited by DDW, whereas proliferation of normal cells was not, suggesting that DDW may influence the D/H ratio in tumor cells, which, in turn, affects the growth rate.

In the present study, we found that DDW increases the S phase cell population and inhibited the proliferation of A549 cells. A greater proportion of DDW-treated A549 cells were arrested at S phase at 72 than at 10 h, as observed by flow cytometry. The cell cycle regulatory system appeared to perceive the D/H ratio, and at the threshold level it triggered the molecular mechanism that finally caused the cell to enter into the S phase (19).

Cell apoptosis via intracellular mechanisms leads to cell death. Many agents have been discovered to treat cancers by inducing an abnormal cell cycle and apoptosis. Thus DDW may have potential as a cancer therapy. Using TUNEL and DNA fragment analyses we showed that DDW significantly increased the number of apoptotic cells after 48 h, indicating that DDW may trigger a molecular mechanism to induce cells to apoptosis. Gyongyi and Somlyai found reduced expression of C-myc, Ha-ras and P53 in six different organs (spleen, lung, thymus, kidney, liver and lymph nodes) of nude mice in the DDW-treated group (21). They suggested that naturally occurring deuterium may be involved in the regulation of genes that play important roles in the cell cycle or tumor development (21). Therefore, future studies exploring the molecular mechanism of DDW-induced apoptosis are vital to elucidate its tumor-inhibitory effects.

Our in vivo results revealed that DDW significantly inhibited tumor growth. However, we do not know whether the effect was caused by cell apoptosis. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of DDW-induced tumor inhibition in vivo.

In summary, we found that DDW exerts effects on the cell cycle and changes in configuration and induces apoptosis in vitro. We also found that DDW inhibits tumor growth in xenotransplanted mice. Collectively, these findings suggest the potential for DDW as an anti-tumor drug with clinical application.

We acknowledge the financial support from the Technology Centre of Luzhoulaojiao Co., Ltd. for the Top Deuterium-Depleted Liquor Research Program.

|

Carney DN: Lung cancer – time to move on from chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 346:126–128. 2002. |

|

|

Nishio K, Nakamura T, Koh Y, et al: Drug resistance in lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 11:109–115. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar |

|

|

Swisher S and Roth JA: Clinical update of Ad-p53 gene therapy for lung cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 11:521–535. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Criss RE: Principles of Stable Isotope Distribution. Oxford University Press; New York: pp. 234–1999 |

|

|

Collins CJ and Bowman NS: Isotope Effects in Chemical Reactions. Van Nostrand Reinhold; New York: pp. 286–363. 1971 |

|

|

Wiberg KB: The deuterium isotope effect. Chem Rev. 55:713–743. 1955. View Article : Google Scholar |

|

|

Jancso G and van Hook WA: Condensed phase isotope effects: especially vapor pressure isotope effects. Chem Rev. 74:689–750. 1974. View Article : Google Scholar |

|

|

Rundel PW, Ehleringer JR and Nagy KA: Stable Isotope in Ecological Research. Springer; New York: pp. 7–9. 1988 |

|

|

Hughes AM, Tolbert BM, Lonberg-Holm K, et al: The effect of deuterium oxide on survival of mice with ascites tumor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 28:58–61. 1958. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Laissue JA, Bally E, Joel DD, et al: Protection of mice from whole-body gamma radiation by deuteration of drinking water. Radiat Res. 96:59–64. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Gross PR and Spindel W: Heavy water inhibition of cell division: an approach to mechanism. Ann NY Acad Sci. 90:500–522. 1962. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Katz JJ, Crespi HL, Czajka DM, et al: Course of deuteriation and some physiological effects of deuterium in mice. Am J Physiol. 203:907–913. 1962.PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Katz JJ, Crespi HL and Hasterlik RJ: Some observations on biological effects of deuterium with special reference to effects on neoplastic processes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 18:641–659. 1957.PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Somlyai G, Jancsó G, Jákli G, et al: Naturally occurring deuterium is essential for the normal growth rate of cells. FEBS Lett. 317:1–4. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Siniak IuE, Turusov VS, Grigorev AI, et al: Consideration of the deuterium-free water supply to an expedition to Mars. Aviakosam Ekolog Med. 37:60–63. 2003.PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Turusov VS, Siniak IuE, Grigor’ev AI, et al: Low-deuterium water effect on transplantable tumors. Vopr Onkol. 51:99–102. 2005.PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Tyrysov VS, Siniak IuE, Antoshina EE, et al: The effect of preliminary administration of water with reduced deuterium content on the growth of transplantable tumors in mice. Vopr Onkol. 52:59–62. 2006.PubMed/NCBI |

|

|

Somlyai G: Defeating cancer! The biological effect of deuterium depletion. Ramnicu Valcea, Romania Conphys. 60–61. 2001. |

|

|

Laskay G, Somlyai G, Jancsó G, et al: Reduced deuterium concentration of water stimulates O2-uptake and electrogenic H+-efflux in the aquatic macrophyte Elodea canadensis. Jpn J Deuterim Sci. 10:17–23. 2001. |

|

|

Berdea P, Cuna S, Cazacu M, et al: Deuterium variation of human blood serum. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyal, Physica. Special Issue. 256–258. 2001. |

|

|

Gyongyi Z and Somlyai G: Deuterium depletion can decrease the expression of C-mys Ha-ras and p53 gene in carcinogen-treated mice. In Vivo. 14:437–440. 2000.PubMed/NCBI |